This paper was the second that I wrote. The photos in the Bulletin were all grey scale but I have substituted the colour versions where I still have them. I will be adding further papers that I have written once they have been published in The Slide Rule Gazette, etc.

Instruments recovered from the wreck of the Earl of Abergavenny

Originally published in the Scientific Instrument Society Bulletin No. 94, September 2007

Introduction

The Earl of Abergavenny was a large East Indiaman of 1440 tons, built in 1796 by Thomas Pitcher at Northfleet, Kent. At the end of January 1805, the ship set sail, on an eighteen-month voyage, bound for Bombay, under the command of Captain John Wordsworth, the brother of poet laureate William Wordsworth. Caught by bad weather in the English Channel, after leaving Portsmouth in convoy, the ships were ordered to seek shelter in Portland Roads. Wordsworth took on a pilot but one hour later the ship ran onto the Shambles bank to the East of Portland. Some hours later the boat floated free from the bank and made for the sandy beach at Weymouth, but the pumps could not cope with the water flooding in and the ship sank in Weymouth bay, at 11pm on 5 th February 1805, with the loss of over 250 lives, out of nearly 400 passengers and crew. Captain Wordsworth was amongst those who perished.

The ship was lying in about 20m of water and her masts were still visible some time after the sinking. On board was an extremely valuable cargo and much of this was salvaged in 1806 by John Braithwaite in spite of the crude nature of diving apparatus at that time. The salvaged items included 62 chests of dollars, valued at £70,000, as well as very many tin ingots, copper bars and pigs of lead. To assist in the salvage operation the wreck was blasted with gunpowder on a number of occasions and in 1921 the Royal Navy blew it up as it was considered a hazard to shipping. This has repercussions on the information that can be gleaned from more recent diving, as we shall see later on.

The ship was lying in about 20m of water and her masts were still visible some time after the sinking. On board was an extremely valuable cargo and much of this was salvaged in 1806 by John Braithwaite in spite of the crude nature of diving apparatus at that time. The salvaged items included 62 chests of dollars, valued at £70,000, as well as very many tin ingots, copper bars and pigs of lead. To assist in the salvage operation the wreck was blasted with gunpowder on a number of occasions and in 1921 the Royal Navy blew it up as it was considered a hazard to shipping. This has repercussions on the information that can be gleaned from more recent diving, as we shall see later on.

The Exploration

For more than 20 years the wreck has been the subject of a detailed exploration by a team of divers, led by Edward Cumming. The wreck has been the subject of a detailed survey and the many artefacts recovered have been catalogued and stored by members of the team. All this has, of course, been done with the permission of the Receiver of Wrecks. In 2005 the artefacts recovered and the events leading up to the sinking were the subject of an exhibition in Weymouth Museum to mark the 200th anniversary of the ship’s tragic loss. The exploration has also been the subject of a television programme in the series “Wreck Detectives“, which produced a theory on why the ship sank. Some of the items are again on display at Weymouth Museum along with other artefacts from the wreck.

The exploration has not just been limited to diving but has also included the use of side scan sonar to provide images of the wreck site. There has also been extensive research carried out on land and a CD (ref. 1) has been produced (in compiled web page format) by Edward Cumming which details the events leading up to the wreck, the salvage operations, the recent exploration and the artefacts recovered.

The exploration has not just been limited to diving but has also included the use of side scan sonar to provide images of the wreck site. There has also been extensive research carried out on land and a CD (ref. 1) has been produced (in compiled web page format) by Edward Cumming which details the events leading up to the wreck, the salvage operations, the recent exploration and the artefacts recovered.

The Instruments

In the following paragraphs I describe the instruments that have been recovered with photographs of each of them. Many of these are drawing instruments, which were used for navigation, and, as only the brass parts have survived, I have shown some of them with complete instruments from my own collection to show what they originally looked like. In fact some of them could only be identified correctly from close comparison with the complete items.

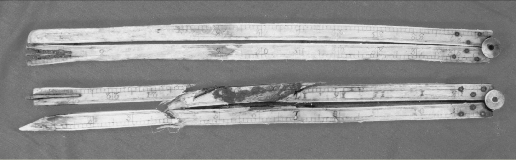

Fig. 1 Two foot Gunter Scale – side 1

Fig. 2 Two foot Gunter Scale – side 2

The Gunter scale (Figs. 1 & 2), made of boxwood, has survived in remarkably good condition. It would have been straight originally and the conservation process has increased the curvature. The scales can all be clearly made out although they do not show very well in the photograph. This would have been used for the navigational calculations in conjunction with dividers, of which parts have also been found (Fig. 10).

Perhaps the most interesting find was an ebony octant (Figs. 3 & 4) on which conservation and restoration work was carried out by Hastings Museum and it is now on long term loan to them. It appears that at least one of the officers used a sextant, however, as filter glass holders (Fig. 5) from one of these have also been found.

Perhaps the most interesting find was an ebony octant (Figs. 3 & 4) on which conservation and restoration work was carried out by Hastings Museum and it is now on long term loan to them. It appears that at least one of the officers used a sextant, however, as filter glass holders (Fig. 5) from one of these have also been found.

Figs. 3, 4. The octant, which has been restored, is now in Hastings Museum. (Both photos by Ed Cumming).

The gauging rule (Fig. 6) appears to be a Brannen rule (ref. 2), whichis comprised of two sections, each being two feet long and hinged in the middle. Folded, the two sections could be easily carried, whilst assembled together they formed a four-foot dipping rod for measuring the content of casks. The two sections could also be used side-by-side as a sort of two-foot slide rule.

Fig. 6. Gauging rule (photo by Ed Cumming).

Fig. 5. Sextant glasses

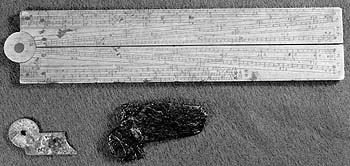

Fig. 7. Slide from a carpenter’s slide rule (bottom) compared with a mid-nineteenth century rule from the author’s collection. (photo by Ed Cumming)

This graduated brass bar (Fig. 7), about nine inches long, appears to be all that is left of a Coggeshall type carpenter’s rule and is shown with a somewhat later rule by Isaac Aston in the author’s collection. One of the uses of the rule was to calculate the volume of a baulk of timber.

“IT13” in Fig. 8. Is instantly recognisable as a compass with a long-joint head and clamping screw for the removable leg. Its brass parts (all that remain) are virtually identical to those of the compass from the same period in the author’s collection. It may well have been part of a pocket set of drawing instruments and would probably have had divider, pencil, pen and dotted line removable (interchangeable) legs. One of these is seen in Fig. 9. Ed was a little surprised, I think, when I identified the bottom left item as part of a compass and not a hinge from spectacles, but showing him a complete example soon convinced him.

“IT13” in Fig. 8. Is instantly recognisable as a compass with a long-

Fig. 8. Compass (top) compared with one from the author’s collection

Fig. 9. Pencil leg from compass (bottom) compared with one from the author’s collection.

Fig. 10. Leg from a hair divider (bottom) compared with 1840s hair divider. (Photo by Ed Cumming)

Fig. 10 shows an item that could easily be identified as part of a compass but is, in fact, one leg from a hair divider. The photograph clearly shows the recess for the spring extension of one of the points. This was fixed in the brass body at the head end by a small screw whilst, at the point end the divider point could be adjusted finely by a screw through the end of the brass body. The accompanying five-inch hair divider from my collection is a little later (1840s, William Elliott) and thus has a sector head rather than long joint and a knurled adjusting screw rather than one with a hand cut wing.

Parts of several ruling pens have been found. This indicates to me that several of the ship’s officers may have possessed their own sets of drawing instruments, particularly as it seems likely that those recovered might only be a part of those originally on board. Many would have been dispersed, or deeply buried in the sand, as a result of the blasting with gunpowder and sea motion. Fig. 11 shows two parts from a ruling pen with a hinged nib. The part on the left is the lower section of the brass handle. The handle of these pens was usually in two sections; the upper section unscrewed to reveal a steel protracting pin, used for marking out. The nib section has lost its steel tips, which would have been soldered into the brass leaves. However it still has its wing screw for setting the line thickness, although it cannot be seen in the photograph.

Fig. 11. – Hinged nib ruling pen (top) with one from the author’s collection.

Fig. 12 shows handles from three more ruling pens. The upper two are from pens with block nibs. As the name suggests these pens had plain steel nib leaves, which were soldered into a block at the end of the brass handle. The pen shown with them, from my collection, is of this type. The bottom handle is probably from a hinged nib pen, as it does not end in a block with two slots in it like the other two.

Fig. 12. – More pen handles.

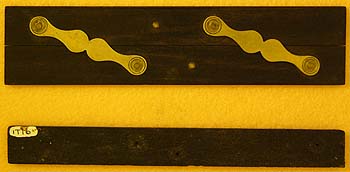

Fig. 13 – Parallel Rule

Fig. 14 – Leaf from a 6” Parallel Rule (bottom), with one from the author’s collection

The parallel rule shown in figure 13 is almost complete. It is twelve inches long and would have been used for navigation in conjunction with a chart. Fig. 14 shows one of the ebony leaves from a six-inch parallel rule. For about two hundred years rules like these were included in sets of drawing instruments.

Fig. 15. – Mechanical Pencil

Fig. 16. Hinge Parts (bottom). Were they from a sector like that above? (Photo by Ed Cumming)

Fig. 16. Hinge Parts (bottom). Were they from a sector like that above? (Photo by Ed Cumming)

Fig. 15 shows the wood case of a mechanical pencil. The pencil is split into two halves for about three-quarters of its length so that the half, shown displaced to the right, can be removed to place a new graphite “lead” in the pencil. Thomas Jones of Whitechapel patented this type of pencil in 1783. A similar one but pointed was found on the wreck of HMS Pandora, which struck the Great Barrier Reef on 29 th August 1791 (ref. 4).

Fig. 16 shows two hinge parts. It is difficult to say whether they came from a sector, like the boxwood one from my collection, or from a jointed rule or a gauging rod. The one on the right is still attached to a fragment of wood. In addition to the items illustrated there were a number of other parts of drawing compasses and fragments of wood from a second gauging rod.

Fig. 16 shows two hinge parts. It is difficult to say whether they came from a sector, like the boxwood one from my collection, or from a jointed rule or a gauging rod. The one on the right is still attached to a fragment of wood. In addition to the items illustrated there were a number of other parts of drawing compasses and fragments of wood from a second gauging rod.

Conclusion

The instruments carried on the Earl of Abergavenny were mainly for navigation, but also were used for gauging and probably by the ship’s carpenter. Both octants and sextants were in use on the ship for obtaining bearings, whilst parallel rules and pocket sets of drawing instruments were used for chart work. Probably at least four types of calculating instrument were used on board, namely the Gunter scale (for navigation), the sector, the Brannen gauging rule (for finding the content of casks), and the carpenter’s rule (for calculating timber volume). The refillable lead pencil was a bit of a puzzle. Portions of more than 20 more were found in the wreck as well as other pencil and crayon fragments. It seems likely that these were part of the cargo.

It would have been nice to draw further conclusions from the position of the various finds. Unfortunately they had been scattered all over the ship by the blasting carried out during the salvage operations and again in 1921, so there is no significance in their positions. None of these conclusions are earth shattering but I hope that it has added just a little to our knowledge.

It would have been nice to draw further conclusions from the position of the various finds. Unfortunately they had been scattered all over the ship by the blasting carried out during the salvage operations and again in 1921, so there is no significance in their positions. None of these conclusions are earth shattering but I hope that it has added just a little to our knowledge.

Acknowledgements

I would particularly like to thank Ed Cumming for his making the items available for photography, for the photographs he has contributed, and for his help, and that of David Carter, in preparing this article. David and Ed are members of the Weymouth LUNAR Society (LUNAR = Land and Underwater Nautical Archaeological Research) which continues to research the historic wrecks in the area.

References

|

1.

|

“The Earl of Abergavenny Historical Record and Wreck Excavation”, Edward Cumming, published as a CD, ISBN 0-

|

|

2.

|

“Politics, Poetry, and England’s Customs and Excise”, Thomas Wyman, Journal of the Oughtred Society, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2006, pages 3 to 8.

|

|

3.

|

“Discover Dorset, Shipwrecks”, Maureen Attwool, The Dovecote Press, 1998

|

4. “Queensland Museum, The Pandora Story” http://www.qm.qld.gov.au/features/pandora/artefacts/02_artefacts.asp