I would like to re-

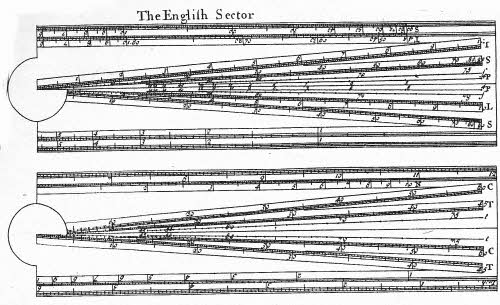

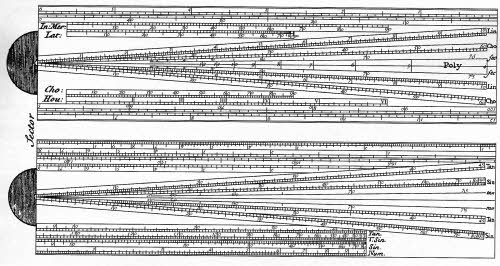

In the early and mid eighteenth century English sectors were generally made of brass and frequently featured an additional hinged plate (the friction leaf) that functioned as a steady and this is a convenient starting point for my chronology because the scales were already becoming standardised. An illustration of both sides of a sector of this period can be found in the modern reprint of Edmund Stone’s English edition of Bionii. This illustration is reproduced in Figure 1. There is also a description of the construction and use of the English sector.

The scales on this sector, which I have divided into two types namely sectoral (radiating from a single point) and parallel (to an edge) are as follows:

Upper side

Sectoral: L, the line of equal parts

Lower side

Sectoral: C, the line of chords

Edmund Stone also observes that there are sometimes extra lines, not shown in the figure, placed in vacant spaces, namely:

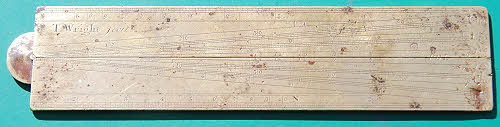

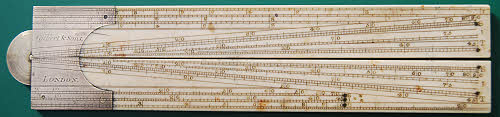

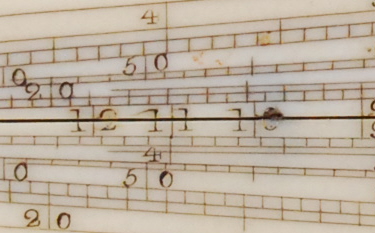

Recently I have acquired a brass sector by Thomas Wright, made between 1718 and 1747 that is shown in Figure 2.

Upper Side

Sectoral: Cho, the line of chords

Parallel: N, Gunter’s line of numbers (logarithms)

Lower Side

Sectoral: Sin, the line of natural sines

Parallel: T, the line of artificial tangents

Outer Edge: A 12 inch ruler divided to tenths

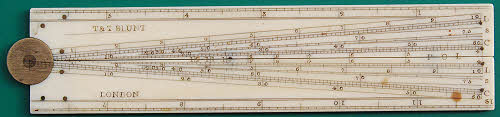

About the middle of the eighteenth century a transition gradually took place, ivory replacing brass. These ivory instruments had arch joints in either silver or, more commonly, brass. In 1775 the third edition of a book by John Robertson was published that again includes an illustration of a sector and again there is conveniently a modern reprint.iv

Figure 3 shows the Robertson illustration. There are more scales than shown in Figure 1. These are:

Upper side

Sectoral: Lin, the line of lines or equal parts

Lower side

Sectoral: Tan, the line of natural tangents

The principal changes are: (a) the interchange of the chord and natural sine sectoral scales to a more logical arrangement, (b) the addition of a line of artificial sines/tangents for small angles, and (c) the four short additional scales, primarily for use with sun dials, that have now become standard.

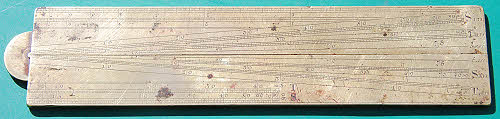

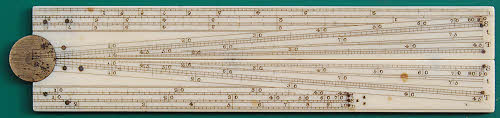

Figure 4 shows an arch joint sector from my collection by Gilbert & Sons that can be dated between 1806 and 1819 according to Gloria Clifton.v

The scales on this instrument, which is actually quite a late arch joint sector, are essentially the same as those in Robertson’s illustration. The sectoral lines are the same but the decimal foot and ST scales have been omitted from the parallel lines and the NUM scale has been extended.

Now arch joint sectors were always (as far as I know) signed on the hinge plate on the side that contains the sine and tangent sectoral scales and thus photographs in books always show this side. However, apart from a few early examples, round joint sectors are signed on the other side that contains the chord, secant and polygon sectoral scales. Peter Hopp’s article, except for the first two figures, only ever showed the signed side and thus the side shown for the arch joint sectors was the opposite to that shown for the round joint sectors. This led Peter to conclude that the scale arrangements were significantly different between the two types. However, I doubted this as I knew that the signed side of the arch joint sector had basically the same set of scales as the unsigned side of the round joint sector. The illustration of that side in Peter’s article was too small and indistinct to show that. His reasoning based on the two Dollond sectors illustrated on page 74 was therefore invalid.

My problem was that I did not anywhere have a picture of the unsigned side of an arch joint sector and until recently I had been unable to purchase or examine one in detail. My recent purchase of the Gilbert & Sons example has closed the loop and yes there are differences. Thus on the round joint sector the four dialling scales (Inclination of the Meridian, etc.) seen on the reverse of the arch joint sector have been deleted and the decimal inch scale has been resurrected as an edge scale along the outer edge of the rule. Also the order of the artificial sine and tangent scales has been reversed.

It now becomes clear why the signature on round joint rules moved to the opposite side. With the deletion of the dialling scales there was now more space on that side to place the “maker’s” name and address. Why were the dialling scales deleted? I suspect this was due to a combination of reasons:

|

·

|

The scales were available on either a plain scale or protractor in the same set of instruments

|

|

·

|

Watches were becoming more accurate and needed less reference to a sundial

|

|

·

|

There was a move from local time to standard (Greenwich) time, especially once railways became commonplace and the telegraph had been introduced.

|

I have been unable to determine whether some arch joint sectors had a decimal foot scale along the outer edges but this may have been so.

In the same manner as the evolution from brass to the arch joint ivory type, there was a gradual transition from the arch joint design to the round joint one. This took place at the end of the 18th and start of the 19th centuries. Early in the 19th century the dialling and navigational scales on plain scales and rectangular protractors were also deleted in favour of more fractional scales for some of the same reasons as they had disappeared, probably a little earlier, from sectors.

All the sectors so far discussed have been six-

Figure 5 shows a sector by T & T Blunt, which dates from between 1801 & 1822. The scales are as follows:

Signature side:

Sectoral: L, the line of lines

Reverse side:

Sectoral: S, the line of natural sines

Outer edge: A foot rule divided into tenths and hundredths

All of my round joint sectors have this scale arrangement. So, who were the actual makers? I had a number of possible theories:

|

1.

|

There were very many different makers of the whole sector

|

|

2.

|

There were a few makers of hinged ivory blanks and many finishers from that state

|

|

3.

|

There were a few suppliers of ivory leaves and also suppliers of brass hinges that the instrument makers bought and finished

|

|

4.

|

The dividing of the blanks was done by a few specialist firms with dividing engines

|

|

5.

|

There were only a few actual makers of sectors (Peter’s theory)

|

|

6.

|

Some ‘makers’ bought sectors from other makers who were better equipped to make sectors.

|

To test these theories might require far more sectors than in any one collection as only a few would come from any particular time period and unsigned ones could not be dated unless they matched a signed one in every detail. To determine that two sectors were actually made by the same maker would require a close or exact match for every detail. These details include:

|

·

|

The length, shape and spacing of the hinge plates

|

|

·

|

The riveting

|

|

·

|

The imprint of the letter and number stamps

|

|

·

|

The star patterns

|

Since the letter and number stamps would quite likely have been made by the instrument maker himself, if there are two relatively early instruments with identical stamp impressions then they must surely have been made by the same maker. To be certain they are identical the whole sector must be examined and the detail must be sharp, a requirement that the web pictures do not meet.

Fortunately I have four sectors that date from about 1810 + a few years:

|

·

|

Gilbert & Sons (arch joint)

|

|

·

|

T & T Blunt

|

|

·

|

Jacob & Halse (from a Shagreen case)

|

|

·

|

An unmarked 4½ inch sector in a sharkskin case

|

Maybe it’s just lucky coincidences but the lettering/numbering on the first two appears a pretty exact match suggesting the same maker for both of these, and the lettering/numbering on the second pair is quite different from the first pair but a pretty exact match again between the two. This suggests that there were at least two makers of sectors in that period who made sectors for other ‘makers’ as well.

To see if any more of my sectors might be compared with one or more others -

|

Signature |

Body |

Hinge |

Size |

Date range |

|

W & S Jones |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1792- |

|

Gilbert & Sons |

Ivory |

Brass, arch |

6 inch |

1806- |

|

Jacob & Halse |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1809- |

|

T & T Blunt |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1801- |

|

Bleuler |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1790- |

|

Unsigned |

Ivory |

Brass |

4.5 inch |

1800- |

|

A Abraham |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1800- |

|

Unsigned |

Boxwood |

Brass |

6 inch |

1800- |

|

Williams & Haydon |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1820- |

|

Watkins & Hill |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1822- |

|

J Archbutt |

Ivory |

Electrum |

6 inch |

1838- |

|

Unsigned |

Ivory |

Electrum |

6 inch |

1840- |

|

Elliott Bros |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1854- |

|

J Casartelli |

Ivory |

Electrum |

6 inch |

1852- |

|

Unsigned |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

19th century |

|

Unsigned |

Boxwood |

Brass |

6 inch |

19th century |

|

Unsigned |

Boxwood |

Brass |

4.5 inch |

19th century |

|

Unsigned |

Boxwood |

Brass |

6 inch |

1860- |

|

Unsigned |

Ivory |

Electrum |

6 inch |

1840- |

|

Stanley |

Ivory |

Electrum |

6 inch |

1870- |

|

Unsigned |

Ivory |

Brass |

6 inch |

1880- |

Examination of the table shows that there are three other sectors from the same approximate time frame as the four already compared. The Abraham one is a pretty good match for the Jacob & Halse one, probably close enough to conclude it is a third by that maker. Holding both these sectors to the light, and ivory being translucent, appears to clinch it. Both sets of metal leaves are actually arched with exactly the same profile inside the ivory -

However, all is not perhaps as simple as that. I next looked at the slightly earlier W & S Jones one. Holding it to the light the hinge leaves are again arched although the profile and length of the hinge plates is slightly different. The lettering and numbering is very similar to that on the T & T Blunt sector and once again the 10, 11 and 12 are much larger and stamped across the edges of both leaves. Holding the Blunt sector to the light again reveals the arch and the hinge turns out to be identical to those of the Jacob & Halse trio.

So, I now have to revise my conclusion; there is one hinge maker supplying hinges to two different sector makers, each of whom make sectors for at least three firms.

The slight differences in the numbers and letters between the Jones and Blunt sectors can be easily explained. The stamps would wear with use and were probably re-

Let’s return to Bleuler. This was the most recently obtained ivory sector, obtained after I had prepared the first draft of this article. There is a picture of another Bleuler sector on page 333 of the Rule Bookviii but this clearly belongs to the Gilbert and Blunt group. Thus we have two sectors from one maker, one of each of the two basic types for that period clearly indicating that they were bought in and not made by Bleuler.

Next in sequence is the J Archbutt sector. The hinge leaves now exhibit a double arch inside and, whilst the lettering/numbering styles have a resemblance to those in the Abraham, Jacob & Halse Group they are not close enough to conclude the same maker. The link has been broken. There are too few signed sectors from the later part of the 19th century to be able to draw further conclusions about makers. However yet another sector has the large 10, 11 & 12 on the polygons scales bridging the gap between the two leaves although the style of the other lettering and numbering does not match the earlier sectors with this feature. It has an electrum hinge with a slight double arch and dates from 1840-

The Casartelli sector again has internal double arch electrum hinge leaves but the lettering and numbering does not closely match others and the sector is actually wider than the earlier ones. The Elliott Bros one may be earlier as it has a brass, single internal arch, hinge. The lettering and numbering style is again similar to that of the Abraham, Jacob and Halse group but it has the large 10, 11 and 12 of the other group so no conclusion can be drawn. It is the same width as the Casartelli one.

The most recent named sector is the Stanley one. The large 10, 11 and 12 on the polygon scales is again present and the hinge is an electrum double inside arch type but the numbers and letters are not a match for any of the other sectors although similar in style. The width is again the same as the Casartelli one.

At some stage in the 19th century off-

My tentative conclusions regarding makers therefore are:

|

·

|

There were two distinctly different styles of lettering and numbering that persisted through the entire period of manufacture of round joint sectors from at least ca.1790 to ca.1900

|

|

·

|

There were only a few actual makers of ivory and boxwood sectors

|

|

·

|

The hinges were probably made by a specialist maker who supplied them to the sector makers, or the sector makers were supplied by a specialist maker with hinged ivory or boxwood blanks

|

|

·

|

The design of the internal hinge leaves changed from single arch to shallow double arch (i.e. a separate arch in each leaf) in the middle of the 19th century and possibly coincided with the change from brass to electrum on the better quality instruments

|

|

·

|

There is still no evidence to suggest who the actual makers were

|

|

·

|

There is little known about the actual manufacturing methods used, there are no known records of these processes, and more research is needed.

|

Finally Dr. Alison Morrison-

ii The construction and principal uses of mathematical instruments translated from the French of M. Bion chief instrument maker to the French king by Edmund Stone……..first published in 1758 and reprinted by the Astragal Press in 1995. ISBN 1-

iv A treatise of such mathematical instruments as are usually put into a portable case………The third edition with many additions. First published in 1775 and reprinted by Flower-

viii The Rule Book, Measuring for the Trades, Jane Rees and Mark Rees, Astragal Press, 2010, ISBN 978-

| Early Sets |

| Traditional Sets |

| Later Sets |

| Major Makers |

| Instruments |

| Miscellanea |

| W F Stanley |

| A G Thornton |

| W H Harling |

| Elliott Bros |

| J Halden |

| Riefler |

| E O Richter |

| Kern, Aarau |

| Keuffel & Esser |

| Compasses |

| Pocket compasses |

| Beam compasses |

| Dividers |

| Proportional dividers |

| Pens |

| Pencils |

| Rules |

| Protractors |

| Squares |

| Parallels |

| Pantographs |

| Sectors |

| Planimeters |

| Map Measurers |

| Miscellaneous |

| Materials Used |

| Who made them |

| Who made these |

| Addiator |

| Addimult |

| Other German |

| USA |

| Miscellaneous |

| Microscopes |

| Barometers |

| Hydrometers & Scales |

| Pedometers |

| Surveying Instruments |

| Other instruments |

| Workshop Measuring Tools |

| Catalogues & Brochures |